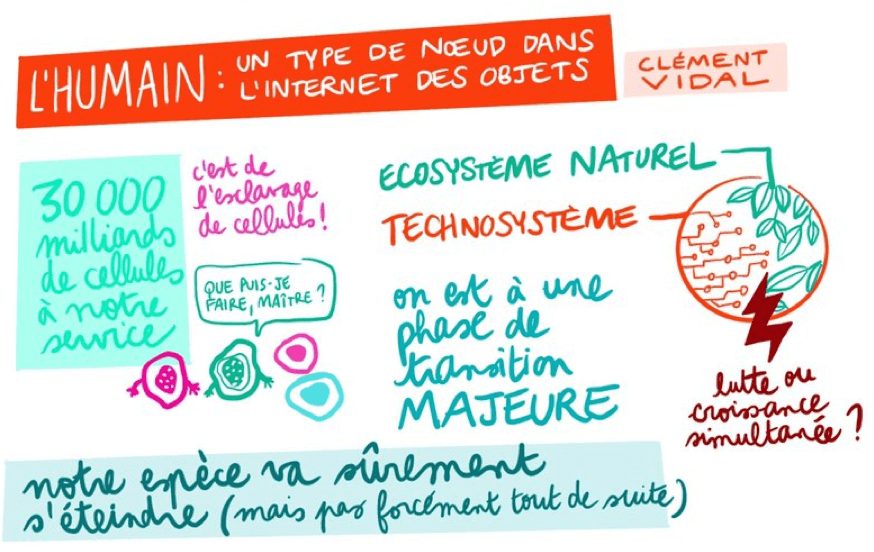

(Abstract illustrated by Louise Plantin)

A perspective of the progress of humanity both dystopian and surprising by the philosopher Clément Vidal.

I will tell you the story of Celine. Celine is hyperconnected. She already has many friends in her network and could potentially have thousands more. Sometimes she realizes she has so many friends that she doesn’t really know them anymore. Celine is well in her bubble, but she is afraid for her privacy. Could viruses exploit his data? Who has access to what she does? Who really influences it?

Celine has tried to disconnect. But this is no longer possible. She is too dependent, and can not go back. Celine, as an individual is rather slow, but she knows that there is an extremely fast information system, something immensely more complex, dizzying that is being built around her.

She asks herself, “Am I surrounded by a kind of superintelligence? Can I understand it one day, with my limited abilities? ”

She heard about the power of GABA, saying they would control the information.

Today, Céline loses her bearings, her identity. She has information that comes from all sides. She is in a confusion between the feeling of seeing her boundaries widen and the feeling of dissolving.

Celine receives too many messages from her environment, too much pressure from her “friends”. She feels useless. Enough is enough. She, unfortunately, sees only one way out: suicide. The post-mortem analysis is clear: Celine is dead … of apoptosis or cell death. Like millions of others today.

Celine was a cell.

A cell that is experiencing the major evolutionary transition between the unicellular world and the multicellular world. But Celine could have been a teenager today. A human who also lives a major transition: between the biological world and the technological world.

The question I ask is: does Celine live a dystopia? Is living a major evolutionary transition a kind of dystopia?

Are we, as individuals integrated into a global, hyper-connected world that we can no longer grasp with our cognitive abilities, do we enter or even create our own dystopia?

To answer these questions, we must realize that our world is not a Walt Disney film where good and evil are clearly separated. In fact, the interpretation of good and evil depends on the scale to which we look at the world. Let’s take three different scales: the individual, the human species and evolution on Earth.

The first scale: the individual

Does Celine the cell live a dystopia from his point of view? Of course, since she’s dying! But if we change the perspective to the scale of our body, we practice slavery and murder … cell! We agree to have 30 trillion cells working to keep us alive. Worse, we accept that our body kills 60 billion cells a day! But if Celine were human, Celine’s story would seem unacceptable to us …

So we have a hard time accepting that we can be part of a kind of planetary brain made up of humans and artificial agents that are smarter than ourselves and who might control us.

The second scale: The human species

Let’s look at the human species. Many are afraid that it will disappear with the technological and climatic changes in which we are. These fears are based on an argument from the theory of evolution that tells us that 99.9% of the species that existed have disappeared. Why should humanity be the exception, the 0.1%, rather than the rule?

From the point of view of the evolution of life on Earth, the extinction of a species is not a drama, but something normal, regular and predictable.

The third scale: Evolution

Evolution has undergone major transitions, such as the origin of chromosomes, sexual reproduction, or multicellular organisms.

Futurologist Kevin Kelly argued in his book What Technology Wants that the invention of language is a pivotal moment in evolution, which has allowed the development of culture and technology. This has led to the technological evolution that you know, from the invention of writing to the press, and recently to the Web and the Internet.

Today Internet enters a phase where it couples with the physical world, on all the planet: it is the Internet of the objects which forms a new techno-ecosystem.

The result is that we live at the beginning of a techno-diversity in the explosion but also of biodiversity in decline. The question for success in this major transition is, therefore: How to develop and regulate together the natural ecosystem and the techno-ecosystem?

With the Internet of Things and the explosion of techno-diversity, humanity is becoming a type of node in the Internet of Things. Humanity may be threatened with extinction, but is also giving birth to technological life. Is this major transition in evolution a dystopia? Yes, if we are focused on the individual or the human species. No, if we take an evolutionist perspective. The real challenge today is to develop new values, and a new consciousness, not only ecological but also techno-ecological.

Biography

References to go further:

- Kelly, Kevin. 2010. What Technology Wants. New York: Viking.

- Maynard Smith, John, and Eörs Szathmáry. 1995. The Major Transitions in Evolution. Oxford ; New York: W.H. Freeman Spektrum.

- Odum, Eugene P. 2001. “The ‘Techno-Ecosystem.’” Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 82 (2): 137–38.

- Vidal, C. 2015, “De la Biodiversité à la Technodiversité.” La Revue Du Cube, numéro 9, pp 65-67. http://lecube.com/revue/refondation/de-la-biodiversite-a-la-technodiversite

Je clique sur le lien “De la Biodiversité à la Technodiversité.” (d’habitude, quand il y a un lien, je clique). Je lis le deuxième paragraphe: “D’une part, nous avons perdu 52 % des espèces de 1970 à 2014 (Rapport « Planète Vivante 2014 » du WWF, p. 146). ”

Je m’étonne beaucoup – c’est une vrai catastrophe! Heureusement Clément l’avait remarqué!

Je vais quand-même vérifier dans le rapport de WWF. Bon.. en fait, c’est pas tout à fait vrai ce que a écrit Clément. C’est Living Planet Index qui a perdu 52% de sa valeur entre 1970 et 2014. Pas vraiment le nombre d’espèces 🙂 Pour info, le LPI est calculé sur l’évolution de la population “for 3,038 out of an estimated 62,839 vertebrate species that have been described globally”

Drôle de négligence pour un chiffre qui supporte la thèse centrale de l’article qui est “passage de la biodiversité à la technodiversité”.

Evgeny,

Merci d’avoir suivi ces deux références et vérifié ce que j’ai écrit. Les références académiques sont en effet là pour que les informations soient vérifiable par tout un chacun, et qu’elles soient corrigeables.

Vous avez raison de noter que le “Living Planet Index” ne mesure que l’évolution de populations, et non pas des espèces. J’ai donc corrigé mon article “De la biodiverstié à la technodiversité” en mentionnant simplement le déclin de la biodiversité (la nouvelle version est ici: https://zenodo.org/record/2599720).

Cela dit, le rapport WWF semble considérer que la mesure de ces populations est un indicateur pour mesurer la biodiversité: “The Living Planet Index also tracks the state of global biodiversity by measuring the population abundance of thousands of vertebrate species around the world. The latest index shows an overall decline of 60% in population sizes between 1970 and 2014.” (C’est aussi curieux que leur chiffre ait changé de 52% à 60% entre le rapport 2014 et 2018…). Sur le fond, je trouve ces chiffres très insuffisants pour mesurer la biodiversité.

Comment mesurer donc la biodiversité à l’échelle planétaire ? C’est une question complexe et difficile, et le rapport WWF le reconnait et le souligne: “But measuring biodiversity – all the varieties of life that can be found on Earth and their relationships to each other – is complex, so this report also explores three other indicators measuring changes in species distribution, extinction risk and changes in community composition. All these paint the same picture – showing severe declines or changes.”

Mon erreur n’affecte donc en rien l’argument que la biodiversité est en déclin.

Et pour revenir au problème de la mesure de la biodiversité, peut-être que grâce à l’explosion de la technodiversité nous pourrons la mesurer de manière plus exacte et dynamique grace à des milliards de récepteurs distribués qui mesurent l’activité biologique de la planète ? Cela pourrait être une application du “Planetary Nervous System” qu’a proposé Dirk Helbing et ses collaborateurs dans le projet FuturICT (Helbing et al. 2012).

Cordialement,

Clément.

Référence:

Helbing, D., S. Bishop, R. Conte, P. Lukowicz, and J. B. McCarthy. 2012. “FuturICT: Participatory Computing to Understand and Manage Our Complex World in a More Sustainable and Resilient Way.” The European Physical Journal Special Topics 214 (1): 11–39. doi:10.1140/epjst/e2012-01686-y. http://www.springerlink.com/index/10.1140/epjst/e2012-01686-y.

Merci Clément pour votre réponse, et mes excuses pour un ton légèrement humoristique de mon message précédent.

Je comprends que la biodiversité n’est pas le vrai sujet de votre article, et que le développement de la technodiversité (ou de la technosphère) ne nécessite pas forcement le déclin de la biodiversité (ou de la biosphère). Ceci dit, quelques remarques encore sur la biodiversité.

En fait, j’éviterais complètement l’utilisation des rapports de WWF pour une simple raison – leur objectif n’est pas scientifique mais politique.

Construire un indice quelconque qui montre un déclin de 60% de sa valeur (un déclin qui a été deux fois recalibré depuis son introduction, comme vous l’aviez correctement remarqué: -28% dans le rapport 2012, -52% dans le rapport 2014 et enfin -60% dans le rapport 2018) – c’est bien pour tirer les sonnettes d’alarme.

En revanche, si on prend en compte que l’indice est calculé sur seulement 5% des espèces vertébrés décrites (3000 sur 62000 espèces), ou sur 0,2% des espèces des animaux décrites (approx. 1 500 000 espèces) on comprend que sa valeur scientifique n’est pas très élevée quelque soit la définition de biodiversité qu’on prend. Et cela sans parler de plusieurs millions d’espèces des autres règnes.

Curieusement, la biodiversité taxonomique observée (c’est à dire le nombre des espèces vivantes identifiées) ne cesse d’augmenter car chaque année on identifie et décrie plusieurs milliers de nouvelles espèces (y compris des animaux vertébrés – il paraît que depuis 1993 plus que 400 mammifères ont été découverts). Cela est bien supérieur au nombre des espèces qui disparaissent actuellement à cause de l’activité humaine, et ainsi la biodiversité connue par l’homme augmente.

Bien sûr, la biodiversité taxonomique objective (si je peux appeler comme ça le nombre total des espèces différents des organismes vivants sur Terre) ne dépend pas du fait que les espèces soient décrites ou pas par l’homme. Mais ici encore la dynamique n’est pas que négative. En effet, l’homme a crée plusieurs milliers des races des animaux domestiques et des plantes, qui contribuent à l’augmentation de la biodiversité, même si ceux ne sont pas des nouvelles espèces. Mais les nouvelles espèces, on en crée aussi – en fabriquant les organismes transgéniques qui stricto sensu peuvent être considérés comme les espèces différentes.

Ainsi, je pense qu’on ne peut parler de la réduction de la biodiversité que si on adopte un point de vue purement “humain” – celui qui confère un poids prépondérant dans la biosphère à des animaux vertébrés “sauvages” (encore une fois, les seuls qui sont considérés dans l’indice de WWF). Alors que il n’y a aucune raison objective pour dire que le génome de rhinocéros blanc soit plus précieux que le génome de virus de variole, ou que le déclin en nombre de certaines populations des oiseaux sauvages ne peut pas être compensé par l’augmentation du nombre de poulets d’élevage.