[This article was originally published in the French edition of the Harvard Business Review]

The third industrial revolution: optimization of resources

The economist Adam Smith identified three key factors for economic growth: labor, capital, and resources. While the first and second Industrial Revolutions were mostly concerned with optimizing labor productivity and capital allocation, the third Industrial Revolution is expected to focus on optimizing resources.

An incredible number of new services are trying to address such inefficiencies in various domains. Apple, and then Spotify changed the way people listen to music. Amazon.com changed the way people buy books and many other products. Airbnb changed the way people rent accommodations when traveling. This list could go on and on.

Because there are significant inefficiencies in accessing talent, it is legitimate to wonder how digital technologies will affect the way in which companies access knowledge and engage workers who have the required skills.

Are talents a ressource like any other? Will modern corporations return to a using a kind of marketplace of talents and skill renting, supported by digital technology? Are we on the cusp of the uberization of corporate jobs?

The answer to this question is yes.

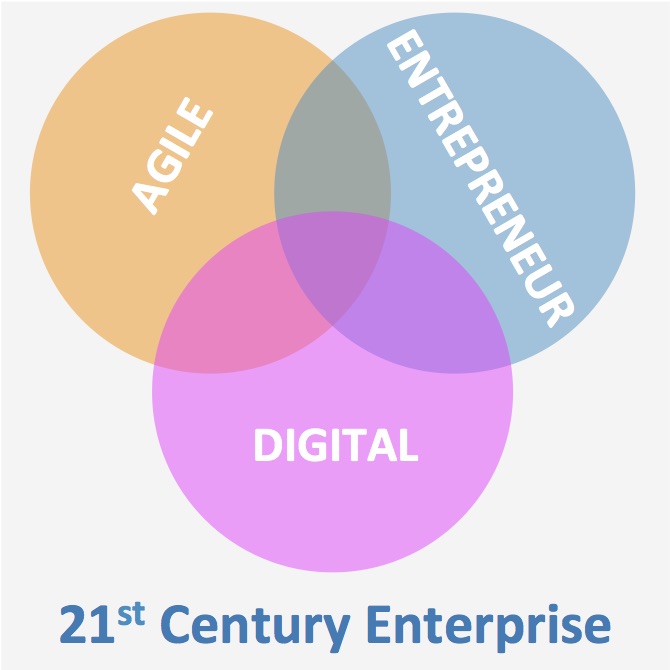

Three trends are converging: (i) companies need more and more agility and flexibility, (ii) the younger generation thinks entrepreneur and sell their talents to multiple companies at the same time, and (iii) digital tools such as freelance platforms facilitate the connection between companies and talents.

Factor #1: how traditional companies are adapting to gain agility

Birth of the enterprise: from a marketplace of skills to employment

A traditional factory, such as a textile factory, before the first Industrial Revolution, differed from today’s factories in two important ways. First, people rented out their skills to the factory – the worker was a supplier. The notion of a work contract did not exist, but rather there was a real marketplace of skills driven by demand (by factories) and supply (by workers). Second, the factory relied on inventions and innovations made by others – the factory did not invest in its future. Inventions were made by individuals, and firms could buy these inventions.

With the first Industrial Revolution and the steam engine, things changed. Firms could no longer rely only on discoveries made by external parties. Instead, they had to take control over their own futures. Firms realized that the activity of invention can and must be collective and controlled.

The enterprise, in its modern sense, is relatively new, having appeared in the late-nineteenth century; its emergence radically changed the classical notions of work, capital, and power. The modern concept of an enterprise appeared in response to the need to collectively organize inventive activities using a scientific approach and to harness innovation. Since that time, technological advances have been organized, managed, and brought to market by enterprises: The enterprise was created to manage complexity in order to build its own future. The marketplace of skills was then replaced by the work contract.

Modern trend: return to a marketplace of talents to gain agility

As we have shown in our recent book Innovation Intelligence and in my article Uberization of Intelligence, companies are facing 3 rapid disruptive trends: the annual volume of new knowledge is growing exponentially, the speed at which a product or a service becomes obsolete is accelerating, and the digital transition of all industries.

These three trends cause an acceleration that forces companies will to become more agile. We are on the verge of the apparition of a new and more dynamic type of company. The concept of project-oriented Dynamic Organization is appearing. The concept of the open, dynamic, and commando (project oriented) enterprise is coming into existence:

- ‘Dynamic’ because in an environment that changes with increased speed, Darwin is at play, and the new species of enterprise must be reconfigurable. Otherwise, it dies. Worse, it dies in good health. ‘Dynamic’ also because the talents it must mobilize to be able to reconfigurate, are themselves in a state of change. ‘Dynamic’ in the final sense that it is the job of the enterprise to quickly train and develop the talents that are merely in transit. Companies will have to take the best advantage from a more and more fluid labour market. They will have to invest in the management and development of a global network of skills.

- ‘Open’ towards the talents that it comprises, because it is the end of full-time and life-time employment. The enterprise that is currently emerging is more and more composed out of freelance workers. ‘Open’ because the workspace itself is being reconfigured: remote working or coworking is becoming more and more common. The smartphone allows a continuous link with work, increasing flexibility in the organization of the work in terms of both time and space.

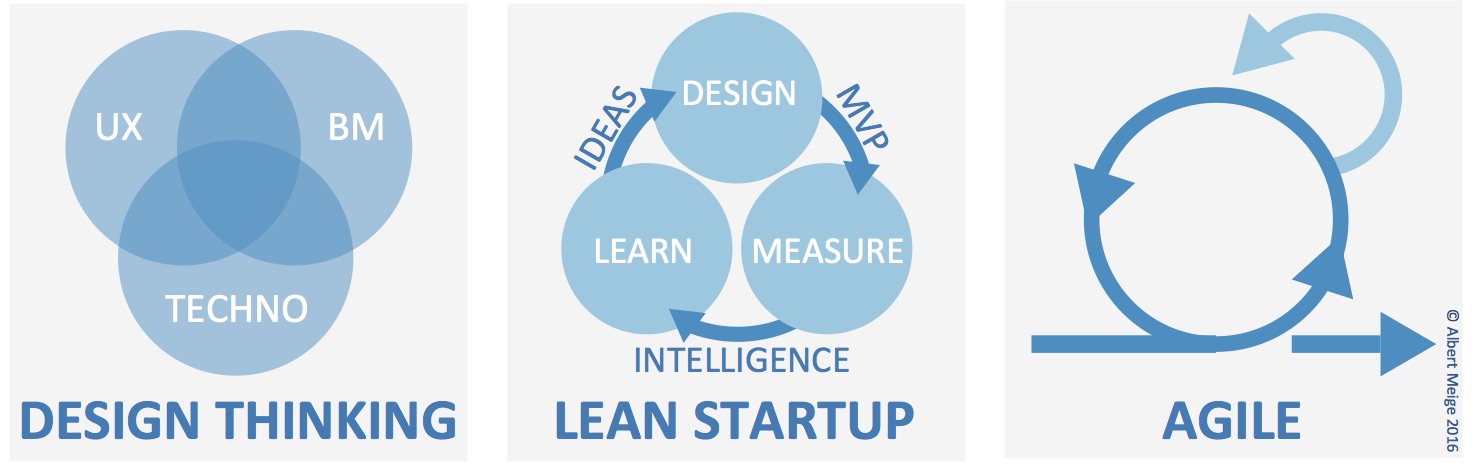

- ‘Commando’ or project oriented. This is the key point of agility: projects that combine complementary internal talents, external talent-entrepreneurs and other types of external entities (startups etc). These commando teams are at the crossroads of Design thinking, the Lean startup movement, and Agile methods.

Tomorrow’s enterprise is still capable of managing complexity and building its own future, but it is also dynamic, open, and organized as a commando.

Factor #1: how the generations Y and Z become entrepreneurs of their professional life and of their education

For younger generations, work has already changed. Younger generations, the Slashers, don’t trust companies. They don’t rely on companies to train them. They change jobs every twelve to eighteen months to gain new experiences, to add lines to their résumé or CV. In fact, rather than a résumé or CV, they have a LinkedIn profile. Talented professionals market themselves. Young professionals are no longer telecom engineers or project managers. Instead, they are developer/designer/DJ or consultant/magician (and I am not speaking about myself!). This “/” is the reason they are called Slashers.

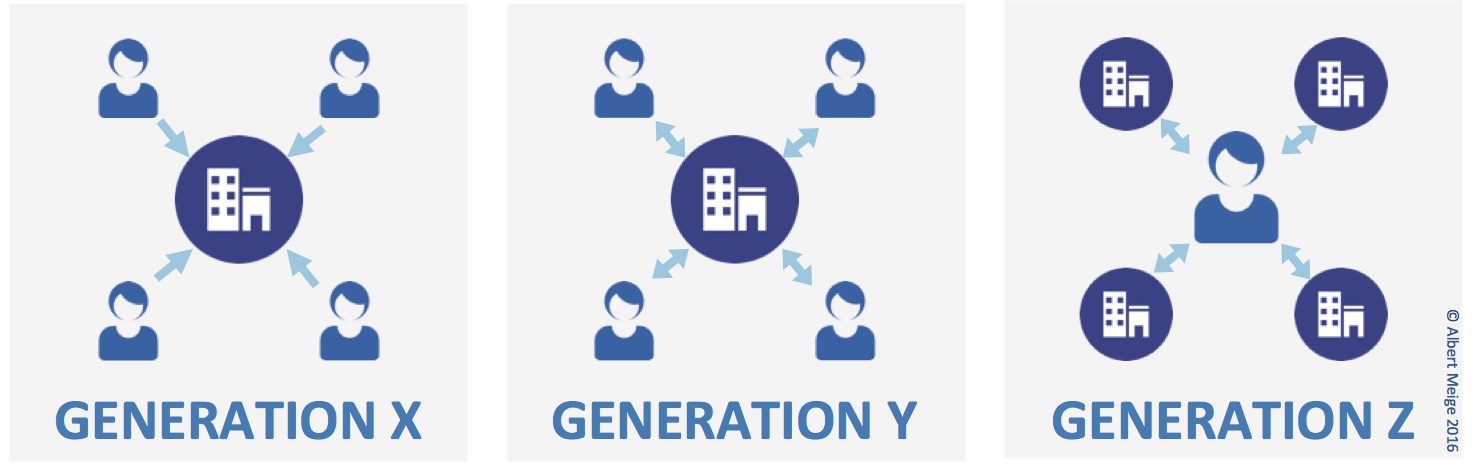

In the Generation X world, companies were deciding to whom they were offering a job, and in return of the job, the employee was giving subordination. In the Generation Y world, companies have first to show what they have to offer, and the talented person will become collaborator if a win-win model can be found. In the world of the Generation Z, talented people are not interested in lifetime contract. They sell their talents to various companies at the same time, during the duration of a given project. For the first time, there are more freelance workers in the US than permanent work contract. The barycenter of employment is not the company any longer, the Z is.

As Emmanuelle Duez would say, “Z is entrepreneur of his/her professional life, but also of his/her education”.

Factor #3: digital tools to connect open & dynamic companies to talented professional

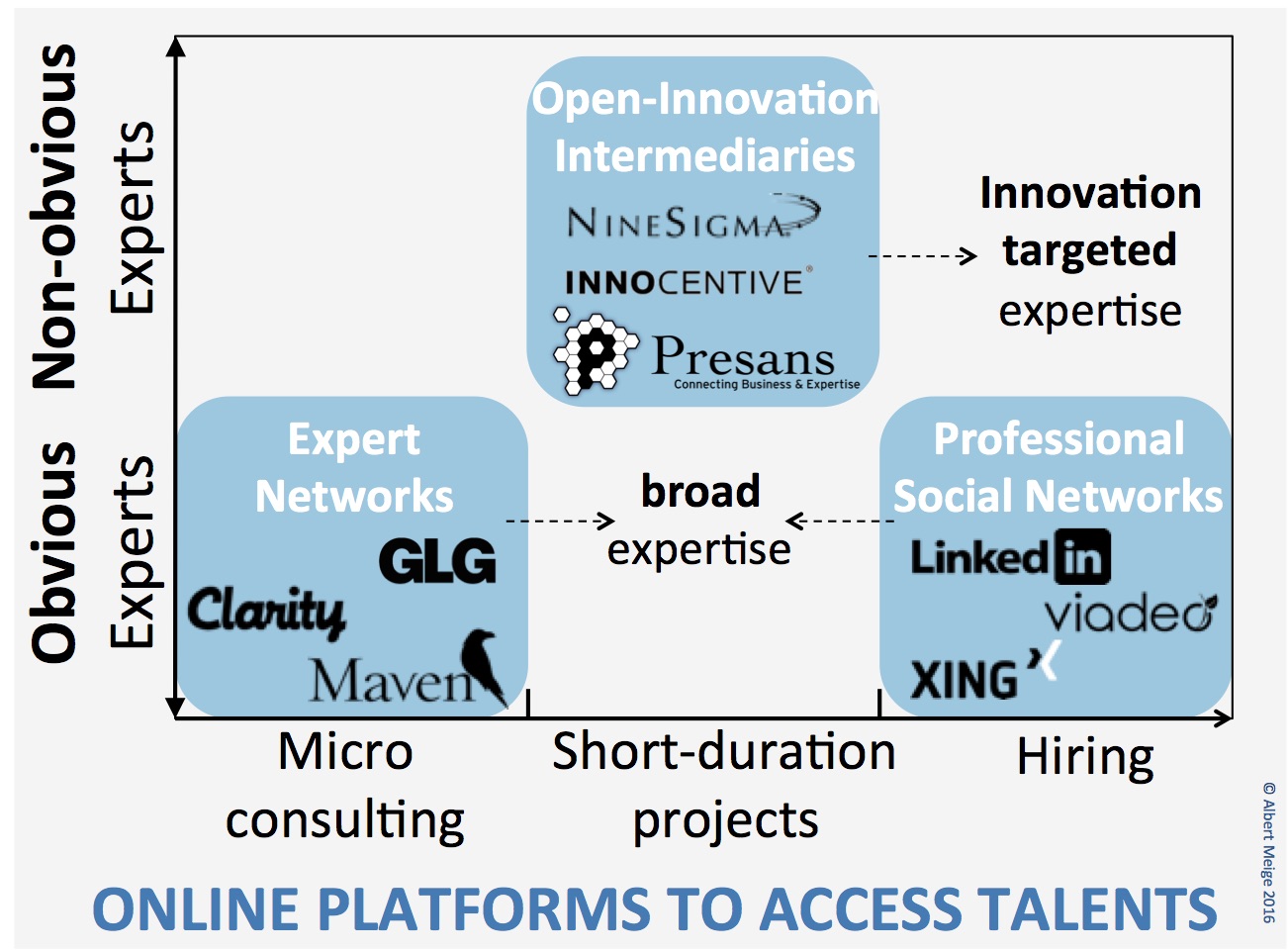

Companies need more and more agility. Young talented professionals sell their skills to several companies during the time of a project. Digital tools help connect these two worlds. On the B2B side, professional social networks provide new tools for headhunting companies to use in finding talented professionals, especially those who are not necessarily actively looking for jobs. On the B2C side, professional social networks provide new tools to young professionals for building their careers based on what other people have done before them. Powerful on-demand matching tools are under development by leaders such as LinkedIn. The objective remains recruitment. But what happens if we push the Slasher trend to its limit? Young talents will offer their expertise not just for a job, but for the duration of a short term project or for a micro-consulting mission. Professional social networks don’t offer the adequate facilitation infrastructure yet. However, other platforms, such as Maven or Clarity — or Presans within its niche —, facilitate not just the matching, but also the relation management between the enterprise on the demand side, and the person with the relevant skills on the supply side. In the short term a convergence will occur between professional social networks and expert platforms.

These digital tools, together with other trends such as the zero-hour contract (an employment contract in which the employer has the discretion to vary the employee’s working hours, usually anywhere from full-time to zero hours), will make work more fluid, more flexible, and less secure.

Conclusion

We are on the verge of a revolution. The notion of enterprise as we know it today will be very different tomorrow. Because agility is becoming critical, companies will become more dynamic, open and project-oriented. Projects will marshal both internal and external talents. External talents will be more and more identified, qualified and engaged through digital marketplaces and they will serve several companies at the same time. Unfortunately, such a result will further stretch the gap between educated people and less-educated people. Depending on the choices we will make, innovation will be synonymous with progress – or not. Disruption is meaningful only if it preserves continuity with fundamental human needs.

***

*

References

[1] A. Meige and J. Schmitt, Innovation Intelligence, absans publishing , 2015

[2] A. Meige and J. Schmitt, Vers une Uberisation de l’intelligence?, Harvard Bus. Rev. France , 2015

[3] A. Meige, Parrot: la rencontre d’un entrepreneur visionnaire et d’un jeune génie bricolant des drones dans son garage, Harvard Bus. Rev. France, 2015

[4] J. Rifkin, The Third Industrial Revolution: How Lateral Power Is Transforming Energy, the Economy, and the World, Palgrave MacMillan, 2011

[5] S. Heck and M. Rogers, Resource Revolution, Amazon Publishing , 2014

[6] B. Segrestin and A. Hatchuel, Refonder l’Entreprise, Seuil, 2012

[7] E. Duez, Comment les générations Y et Z voient le monde de l’entreprise, Challenges, 2015