Start-up companies are extremely active at the frontier of applied science. Their origins are diverse, but the following scenarios are most common:

- Spin-off from a public research organization. Prior to the effective creation of a start-up company, the team is often incubated in source public research organization. Today, entrepreneurship is strongly supported by most governmental agencies.

- Direct or indirect spin-off from an existing company. When a project is determined to be outside a company’s strategy but the project has strong potential, its champions are sometimes allowed to pursue the project on their own by forming a start-up firm. In such case, the existing company typically retains a stake in the spun-off start-up firm in order to reap a benefit from the potential success that it initiated. Sometimes the spin-off is less peaceful; key engineers may resign and become independent entrepreneurs.

- Students or groups of students, often who have not yet finished their education, often start business around an idea, frequently but not necessarily based on the Internet. Examples include Pascal Zunino, described in the Parrot case, and Leetchi.com, described below.

- Former start-up firm that failed but is later reborn in a different form with an improved business model, thanks to lessons learned from the experience.

It is difficult to keep track of the action in this vibrant and ever-changing landscape of start-up firms. They appear, change names, and then die or are acquired quite rapidly. In the early phase, they have little visibility and may focus on only one or two referring customers. They have great potential for creativity, and by submitting their ideas to the market at a very early stage they provide valuable knowledge.

More than 80% of the innovation managers we interviewed emphasized their high degree of interest in the fertile world of start-ups, but at the same time they all stated that it was difficult and time-consuming to search and find interesting picks in this informal, complex, and ever-changing landscape.

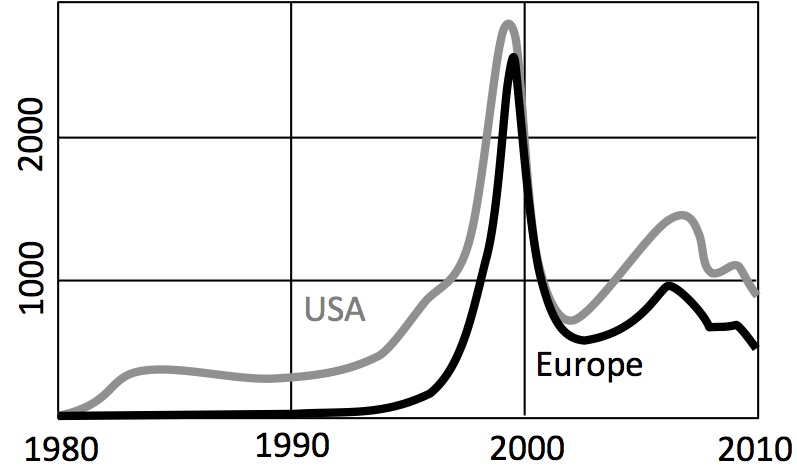

The chart shows the rate of start-up firm creation in Europe and the United States, as estimated from first venture-capital investment deal. The peak around the year 2000 corresponds to the famous Internet bubble. Data is from Dow Jones VentureSource. The data is only indicative, because not all start-ups are funded by venture capital.

A start-up is a young, small company that has virtually no revenue and is investing in developing an innovative product or service. The risk pattern for start-up firms is similar to that for all innovation projects: the probability of success is relatively low, but success creates value of ten or more times the initial investment. It is difficult to count innovation-driven start-ups. They are sometimes lumped together with the entrepreneur’s other ventures, such as opening a restaurant. In the figure we have counted only the start-ups supported by venture-capital firms, but the trend associated with these start-ups is likely indicative of the trend for start-ups financed by other means. As shown in the figure, today about 1,000 start-ups are launched in the United States each year, slightly fewer than in Europe. A start-up launch, as shown in this figure, is proxied by the company receiving its first round of venture-capital funding. This figure also shows the Internet bubble in the year 2000, during which the rate of start-up creation was more than three times higher than it is today. The hype that generated the Internet bubble was based on the digital innovation wave. This same theme, along with medical science, populates the majority of today’s start-ups. As we will see later in this book, venture capital is still fond of digital innovation. This digital topic is still popular for start-ups and approved by venture-capital firms in part due to the shortcomings of large, established companies with regard to the digital revolution; the large, established companies have left so much room that start-ups stand a good chance of finding a market slot and creating value. This observation is less valid in the mainstream business-to-consumer (B2C) arena, because Google, Facebook and others are in the competition, but it will remain true for years in niches and in the business-to-business (B2B) arena.

Also demonstrated in the figure is the fact that Europe almost did not exist on the venture-capital scene before 1995, but it is now gradually catching up. Europe’s start-up creation trend began in northwestern Europe, perhaps because the Protestant culture is more keen on entrepreneurship. Scandinavia, in particular, is booming today, and we have highlighted one example (see the inset below). Israel is also a popular place for start-up creation today. In Asia, the start-up culture is at an early stage of its development; however, clear signs of activity are coming from South Korea, Taiwan, mainland China, and India. According to experts, conditions are favorable for Brazil and Russia to soon join in this new form of innovation.

Coworks was founded in Stockholm in 2010. It has developed a freelancing job website focused on the creative professionals. Cofounders Mattias Guilotte and Henrik Dillman want to create a social network.

As mentioned above, it is difficult to count the start-ups in operation. We propose the following approach to making a rough, low-end estimate: assume approximately 2,000 start-up creations per year worldwide (based on the figure plus an estimate for the rest of the world) and an average five-year life for a start-up company (some of these firms die, some are acquired, and some become profitable and endure). By multiplying 2,000 start-ups by the average five-year life, we arrive at a low-end estimate of 10,000 active start-ups around the globe. Incorporating a rough guess of 10 skilled employees, on average, in each start-up, we estimate an army of 100,000 skilled persons employed by start-ups; the true number is probably significantly larger, perhaps twice that many.

Leetchi.com, founded in 2008 by Celine Lazorthes, is gaining momentum. The website is a digital tool for social communities to use for collecting funds.

Compared to the estimated five million researchers in the world (academia and industry), this remains a relatively small number. But this 2–4% minority is growing and is composed of creative activists who are battling hard at the frontier where knowledge intersects with business. Their relative effect on the future economy far exceeds this small ratio. Most start-ups, like our examples in the inset above, focus on the digital economy, but a decent proportion of them are in more traditional businesses, from MEMS to beauty cream. And it’s important to note that the knowledge created by start-ups is not only technical. As emphasized by Henri Chesbrough, start-ups are willing to consider any business model, because they are tied to none (in contrast to established companies). The knowledge created by start-ups, then, is not only technical but also related to the market’s response to alternative business models.

An estimated 100,000–200,000 creative persons, enthusiastic and fully involved in their projects at start-up firms; this is not insignificant, particularly given that they are innovation activists. Unfortunately, start-up firms’ knowledge is the most dispersed knowledge. Exploring the start-up nebulae is a difficult challenge: start-ups belong to the most fragmented fraction of frontier knowledge.

***

This article was initially published in the book Innovation Intelligence (2015). It is the first section of the fourth chapter.

From decision to action

The Conciergerie helps you engage on demand top level experts for industrial innovation