In the previous articles of this series, we wrote about Internal Knowledge, Time Horizon, Frontier Sciences, Academic Knowledge, Learning and Experience, and Parallel Worlds. Here we deal with Risk Management.

Innovation as a risky venture

Innovation is the process of pushing a new concept toward its implementation in the society with the objective of creating value. At least in the early phase of its process, innovation is always an endeavor with a low probability of success. Innovation is risky, because it explores paths that have not yet been visited or mapped and in which the presence and location of treacherous obstacles have not been recorded. Uncertainty is the key, unavoidable aspect of innovation.

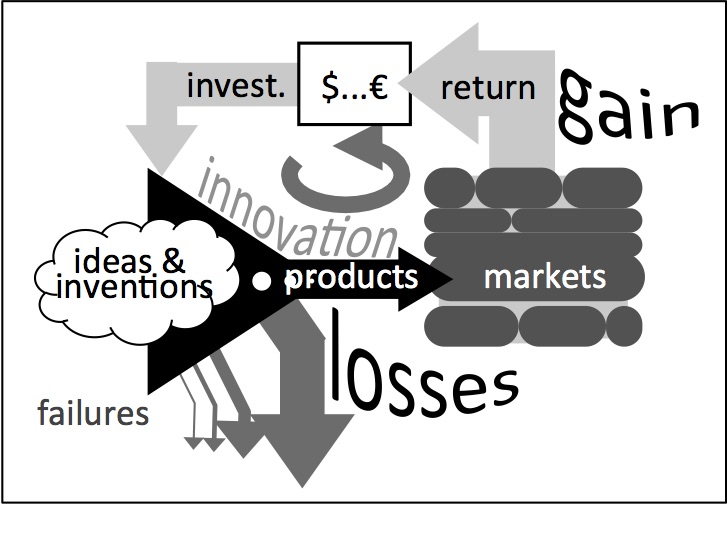

The economics of innovation can only be regarded as a statistical average of the performance of the innovation cycle represented in the figure below. At the core of the process, the innovation cycle itself can be represented by the famous funnel into which many ideas are introduced. As an innovative project progresses along its individual path, a better understanding of the ideas is formed, and, unavoidably, a large fraction of the ideas are determined to be non-viable so are dropped. The abandoned ideas may be seen as failures and the resources that were used to foster them as losses, but hopefully all is not wasted. From failure can come valuable learning, a benefit that accounting may not take into consideration.

Innovation cycle of the economy. The system generates large losses that must be offset by sufficiently large successes.

A fraction of the projects continue along their innovation courses and become products that enter the market and generate the premium revenue associated with an innovative item. A portion of the financial gain can be reinvested in new, innovative projects, perpetuating the innovation cycle. If gains exceed losses, the innovation cycle continues. Due to its large losses and the low probability of successes (as noted, at least in the early stages of each project), innovation is like gambling. This metaphor raises the following key question:

Is there a winning system for the gambling game called innovation?

The answer is both yes and no. There is no simple system, no miracle algorithm, for eliminating risk from the innovation cycle. Eliminating risk would mean avoiding newness, and that would destroy the very substance of innovation. However, there are a couple basic rules that separate the winners and the losers at the innovation game:

· Maximize gains by collecting the maximum value that can be created by successful innovations. Recommended ways of achieving this include patents, an optimized business model, solid market projections, international distribution, speed to market, and spin off or licensing in situations when the innovation does not fit in the company’s strategy.

· Minimize losses. This does not mean that only riskless or low-risk projects should be pursued but rather that the risk associated with each project should be carefully and objectively managed. The concept is summarized precisely in a well-known motto found in many management books: “fail fast, fail cheap, fail often.” Although, like many authors, we do not like the impression of ease that may be suggested by this motto. Managing innovation risk does not mean simply dreaming up ideas—it is difficult, intensive work that requires focusing on the sources of uncertainty that quench the project’s viability, finding the smartest and fastest way to shed light on such key factors, and accepting the heartbreaking decision to cancel a project early when its probability of success is low.

The stage-gating approach to risk management

The process leading to killing a “good idea” with a hidden flaw deserves attention as it is based on knowledge and requires expertise to be done efficiently.

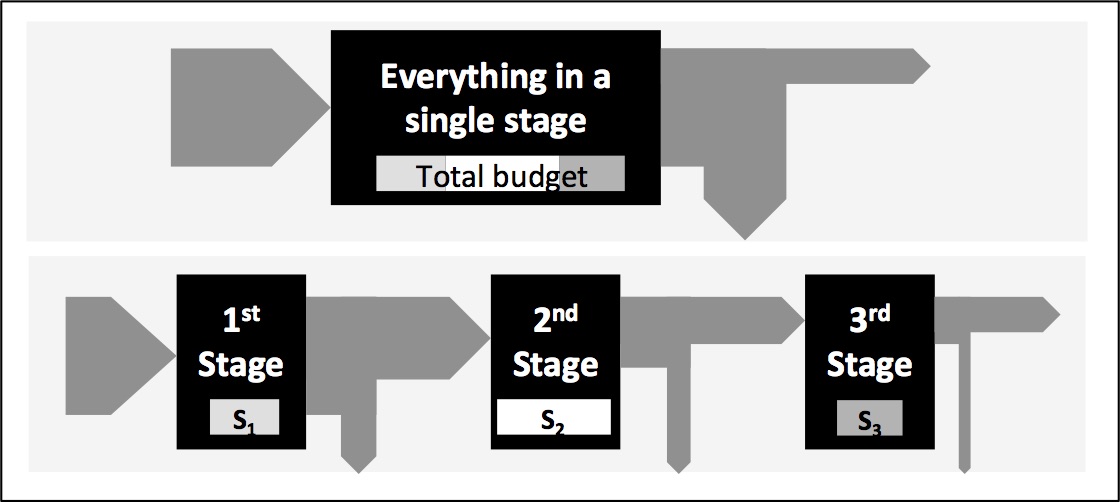

A creative idea is born in an environment of uncertainty. A fool will attempt the daring exercise of assigning a budget to the venture and then will rush straight into the fog and blow through the entire project budget. Instead, it is highly recommended that you do some planning, even though the very concept of planning may be surprising in such an environment of uncertainty. Our recommended approach is to first list all of the unanswered questions that are critical to the viability of the initial idea. Then, make a list of killer questions, and reorder the question in a hierarchy with the most risky at the top of the list. The creation of this list is where innovative genius is revealed, by combining experience, business sense, and operational knowledge. Finally, address each of the questions in sequence. Such a rational, step-by-step approach to the planning phase of innovation is a type of stage gating.

Schematic of an innovation process in a single stage (the top of the figure) or divided into three stages, each with a specified failure risk and budget. The gray arrows indicate movement through the process in the case of success (movement from left to right) or failure (movement down to the recycling bin).

By addressing the most risky aspect of an idea first, the average spending per project is minimized, as shown in the figure on the right. Indeed, if a project is cancelled after its first killer question, the most risky, receives a bad answer, then only a relatively small portion of the budget has been spent and the rest of the budget and resources can be reassigned to other, more promising projects. This is a key improvement in the efficiency of the innovation cycle. Killing non-viable projects quickly is rarely a natural approach, however, as a project manager tends to champion his or her idea and is often reluctant to consider in priority the idea’s potential weaknesses.

Now let’s focus on knowledge in relation to innovation process planning. For an innovation project team, any question that is raised in an environment of insufficient knowledge bears significant risk. The lack of knowledge may result in a flawed concept or suboptimal project planning and strategic orientation. As a result, in the earliest stages of the innovation process a team should consciously go against its natural tendency, and address any priority areas for which it has insufficient knowledge.

Indeed, at these early stages project teams are often victims of type of streetlight effect. They are tempted to tackle first the aspects of the problem for which the team already has sufficient skills and knowledge and postpone the more unknown aspects.

Calling on an expert in the desired specialty is probably the fastest and safest approach. This injection of specialized, outside expertise into the project should take place as early as possible, ideally while the project is still in its early evaluation phase. Based on the expert’s input and the project team’s analysis, the team will be able to construct a detailed plan for how, where, and when the team will integrate in-house and activate the required new knowledge.

Unexpected obstacle

Even when care and attention is dedicated to the planning phase of a project, there still exists the chance that a treacherous obstacle, missed in the list of killer questions, is hidden in the fog of uncertainty. The issue may be discovered in a late stage and pose a severe threat to the project by suddenly increasing risk, delay the schedule, or increasing the budget. Failing to identify some difficulties during an innovation project is normal—it is a natural consequence of the basic uncertainty associated with innovation. However, an unexpected obstacle is more likely to appear in situations in which the driving team has insufficient knowledge. Regardless, when such an unexpected problem pops up, it creates stress and induces an immediate feeling of urgency in the entire team. The project is already in progress, it has a significant daily fixed cost, and, as a result, the unexpected obstacle must be addressed rapidly.

On such occasions, companies rarely hesitate to call upon external expertise. The expert is then seen as a proverbial firefighter. There are several technical sectors (software development, Internet security, corrosion consulting, acoustic engineering, and so forth) in which experts regularly act as firefighters, but any area in which the team has insufficient knowledge can cause an unexpected obstacle to arise during an innovation project.

***

This article was initially published in the book Innovation Intelligence (2015). It is the third section of the third chapter.

NEED A QUICK ANSWER TO YOUR TECHNOLOGICAL QUESTION ?

The Conciergerie platform sets up your call appointment with a Presans-vetted international expert within few days